We discuss a broad range of issues that are often investment-related, but not always so. We call it a 'thought blog'. Sagacious: Having or showing keen discernment, sound judgment, and farsightedness.

2007: A Look Forward

I will quit waxing philosophical to deal with what I look for in the stock market in the year ahead. What will the market do and what companies or sectors might do well in 2007?

I must qualify my forthcoming statements by saying that I don’t think broad market predictions are worthwhile. If I get any of this right, it will have been from dumb luck and not clairvoyance. Putting one’s thoughts down on paper (or blogs), though, allows a person to reflect on past statements and determine what was right or wrong about an analysis. It’s useful to document one’s investment thesis or underlying assumptions when making investment decisions or developing projections. To do so allows one to more readily learn from past mistakes and to develop better analytical processes to hopefully avoid similar mistakes going forward.

The contrarian in me likes to look at companies that have been beaten down in the current year to find future winners. As I look at the Dow 30, I see five companies that haven’t really moved much this year. 3M (MMM) and Alcoa (AA) were basically flat; Wal-Mart (WMT) is down 2.9%; Home Depot (HD) is down 4%; and Intel (INTC) has been the biggest loser, down 19%. The worst performing sectors in the S&P 500 Index were information technology, health care, and consumer staples, though they are all higher.

Let’s start with next year’s winners. In this year’s discard pile, there are two I like – Wal-Mart and Home Depot. Each company is a past stock market darling whose stock has fallen on hard times. Both trade at a valuation that discounts overly pessimistic views yet these two companies are still growing well, enjoying high returns on capital, growing dividends, and share buybacks. I expect these two companies to benefit the long-term investor if purchased at these levels, though I will not give a timetable on when they will rally.

In the coming year, I suspect that the domestic stock market will do the better than most developed international markets. Emerging markets may continue to do well, as there remains an abundance of capital in search of investments. This depends on lot on how the prices of basic commodities hold up, as they are the dominant source of emerging market exports. U.S. investors in international markets in 2007 may face a headwind in the form of a rising dollar, which lies in contrast to this year. As of today, the MSCI EAFE Index is up 22.3% year-to-date in dollar terms, but in local currency it’s up only 12.7%. So nearly 10% of its 2006 return has been due to the declining dollar.

The dollar has been trampled this year and it seems all of the talk I hear about it is bearish. So I’ll take the opposite view and say the dollar will be up in 2007. A wild card is whether the Chinese will allow their currency (yuan) to float. If so, this would help reduce our trade deficit, which is bullish for the dollar. In addition to the dollar tailwind (for U.S. companies), financially strong large and medium sized companies stand to benefit the most if credit markets tighten significantly and world economic growth slows.

I think we could have another up year in the market, probably in the range of 8-12%. But I don’t think we can get this upside with the low volatility we’ve had since August. I think we’re going to be able to buy the market at lower levels, which obviously increases the upside for an investor buying on dips. That said, I don’t advocate trying to time the market. I for one am no good at it. I DO advocate paying close attention to the prices paid when investing in individual companies. If the market is not offering you a margin of safety, money markets pay you nearly 5% to sit on the sidelines.

I don’t see a lot of talk about P/E multiple expansion for next year. In fact, I hear many pundits on CNBC saying “we don’t see much multiple expansion in 2007.” This leads me to believe we will have some, but I think this will help to cushion returns, because earnings growth will not be as robust as expected. Multiples may expand as earnings grow moderately. A 15.5 forward P/E only has to move to 16.28 to add another 5% to the market's total return.

The consumer is likely to remain strong in 2007. There is no reason to believe otherwise or to bet against them. Yes, the savings rate is flat-to-negative and home equity extraction has slowed significantly. But workers in general have not shared commensurately in the prosperity corporations have enjoyed recently and labor markets are tightening, leading me to conclude that wage levels will continue to ratchet higher and provide additional discretionary income.

Of course, discretionary income depends a lot on what energy prices do. Higher oil, natural gas, and gasoline prices leave less discretionary spending for the consumer. So where will prices go in 2007? Well, the low supply/growing demand argument continues to have merit. I’m not sure where the “normal” prices for oil and gas are, but under normal circumstances prices should approximate the marginal cost of production. The marginal cost of production is probably in the $20-40 dollar range (yes, it’s a wide range because its difficult to know for certain). The marginal cost is probably on the higher end due to higher drilling costs and a tight labor supply that have left the industry with higher incremental production costs. The prospect of serious supply disruptions keeps a premium on oil prices that I don’t think with abate soon.

It will be interesting to see how it plays out. Happy New Year.

Christmas Weekend Wisdom

- Warren Buffett

Generic Approved For Key Biovail Drug

Make no mistake; this is a big setback for the company, but one that the market was clearly expecting, judging by today’s mere 2.3% share price retreat in reaction to the news. The company is dealing with this – reducing their fixed cost based by eliminating their U.S. workforce and buying in all of their debt. While the share price has come up quite a bit to reflect renewed confidence in the company’s future, at current levels there doesn’t seem to be a margin of safety in the shares. This makes me wary of new investments at this point. But with expected dividends totaling $2.00 in 2007, the total return assuming no share price movement is a little under 10%, a satisfactory return until new products again boost Biovail’s revenues and reinvigorate growth.

Biovail Slims Down

These actions raise some questions. One problem that stuck out to me is that they’re forecasting roughly $2.00 in operating cash flow for 2007, which happens to be the exact amount they’re going to be paying out in dividends over the next 12 months - or rather, "contemplating" paying that amount, according to the press release.

They’ve got more than enough cash ($630M) to buy in their existing long-term debt ($400M). Doing this will reduce interest expense (and add to cash flow) about $.30 per share. But they’ll also need more cash for ramped-up R&D spending and severance related to the layoffs of its U.S. salesforce (12% of the total workforce). They’re going to be spending about $125M (roughly $0.75/share) each year over the next four years for R&D. And they’ll book restructuring charges related to the layoffs in the fourth quarter, but the cash outflows related to this will not be confined to one period.

All things considered, unless they get a significant new product on the market, I think they’re going to need more cash than they’re currently generating to maintain their announced goals for a length of time. The $1.50 annual dividend plus $0.50 special dividend totals $2.00 per share. With projected operating cash flows of $2.00-$2.12 per share and an additional $0.30 in interest savings, I get to only around $2.40 in annual operating cash flow on the high end (my hunch is that guidance already factors in the interest savings). They’ll save on compensation costs in future periods, but near-term severance costs will use cash. Paying out more than the cash flow they generate should work this year with no problem, because they’ll have quite a bit of cash left over after buying in debt. But if capital expenditures are higher than expected, current products do not perform as projected or those in the pipeline don’t take off, they may have to increase short-term borrowing or cut back their dividend plans in another year or so.

This recent action makes me think that management is preparing for something on the horizon – like a private equity deal or acquisition. Why else would you elect to become debt free and start paying nearly all operating cash flow as a dividend? Does the founder/chairman/largest individual shareholder want to exploit the low price and take the company private for himself? If he wanted that, he’d be more likely to use the extra cash allocated for dividends to reduce the outstanding share count. It seems to me the founder wants to get the cash off the balance sheet in the event a buyer emerges to buy the whole company at a price he considers undervalued.

An Opportunity to Buy Pfizer on the Cheap?

The concern now is with pipeline replenishment and thus revenue replacement. The company has frequently added to its product lineup with acquisitions, and this recent development may pressure them to be more aggressive in this space over the next few years. Meanwhile, with the prospect of declining revenues, the company is focused on cost reduction, having announced a week ago that it’s cutting its global workforce by 20%.

The bottom line is that even without torcetrapib in the pipeline, Pfizer still has a decent drug pipeline and cash to buy more drug assets. It’s a very financially strong company with a hefty dividend and tons of free cash flow. If shares drop 10-20%, as many analysts are expecting, it'll be a good opportunity to buy the stock. If the shares are down that much we’re talking about a stock with a 9-10% free cash flow yield, trading at 11-12 times forward earnings with a 4% dividend. At that price, a long-term buy and hold investor is likely to achieve above-average results.

WB Wisdom

- Warren Buffett

Value Investors Catch a Break

Today, the S&P 500 experienced its largest loss in 5 months, down almost 1.4%. This is the fifth largest decline this year and one of only 13 days this year that were down more than 1.00% (we’ve had 15 that were up more than 1%). While I would not say that stock market valuations are getting out of hand, after its recent run-up it’s nice to see a day where the stock market is down. It reminds us that volatility is something to be expected when investing in stocks.

What has troubled me over the last couple months is the low volatility of the recent rally. We have not had a day down more than 1% since July 13th. July 12th was also down more than 1%. Today, the decline was broad-based, with some 90% of the S&P trading lower and 27 of the 30 Dow stocks declining. Is this the start of a “correction”? Maybe or maybe not.

In the seven trading days beginning with July 12th, the market was down about 1.8%. In the seven trading days starting with June 6th, the S&P 500 was down 5%. For 2006, after the first -1% drop in a while, two-thirds of subsequent seven-day trading periods were followed by market declines. The average performance this year for the seven days starting with a –1% day? Down 2.3%.

I’ve got to say it’s a relief to see that the market can actually go down. Though undervalued stocks can be found in every type of market – think Apollo (APOL) – a couple more days like this and we might find a few more stocks in the bargain bin.

Ability to Pass Up Investments is Key

Another crucial part of making good investment decisions is being aware of your own biases. These biases are well-documented in behavioral finance: overconfidence, hindsight bias, overreaction, belief perseverance, and regret avoidance, for example. Knowing where you decisions are coming from helps to determine whether your choices are truly objective and rational, not overly influenced by your own biases.

Dell Up, Let's Upgrade It!

Today, Bear Stearns and Needham upgraded Dell. With these actions, they’re telling their clients that, since the stock is up and the future seems clearer, now is the time to buy. In other words, "Wait to buy it until it goes up." This is the exact opposite of when an analyst should be recommending a "Buy." I'm glad I don't have an account with them.

These analysts wanted to see evidence that a turnaround is in place before issuing the upgrades. This C.Y.A. mentally may have cost their clients a great opportunity, as Dell is a company whose stock over the past few months has presented a tremendous value. And today it’s up around 10%. Where were the “buy” ratings before? Unfortunately for the firms’ clients, waiting until the point when everything is clear can reduce the eventual profits they earn. Uncertainty creates opportunity.

Dell will continue to invest in customer service, new product introductions, and international expansion. In the press release, management says future operating and financial improvements will be “nonlinear.” This simply means that capital expenditures will sap some near-term earnings and cash flows. As a long-term investor, I feel great when a business invests in its future growth, especially when incremental investment returns are as high as Dell’s. Managing with too much focus on the short-term can impair a company's competitive advantages and be detrimental to shareholders.

Dell is generating massive amounts of free cash flow, enjoys 40%+ returns on equity, has almost no debt, and carries significant insider ownership. The company finished the quarter with almost $12 billion in cash – this amounts to 20% of Dell’s market value as of yesterday’s close. There is still quite a bit of upside from here.

Disclosure: I own shares of Dell.

Thoughts From W.B.

- Warren Buffett

Dow Approaching Overvaluation?

The Dow and the S&P 500 made new highs again today, continuing the theme of the last month. After another record day I think it’s prudent to look at where valuations stand. The Dow currently trades for over 19 times forward earnings, assuming a consensus 12% growth rate from present levels. This translates to a forward earnings yield of just 5.18%. This happens to be lower than the Fed Funds rate and about on par with the yield on money market accounts. Given the option between a fully priced market and a virtually risk free money market account yielding the same amount for the year ahead, the choice seems clear. From a Fed model standpoint, stocks are fairly valued.

By the way, the S&P 500 looks a little more reasonably priced at around 17 times projected earnings, translating to an earnings yield of around 6%. It seems the Dow fetches a richer valuation than the S&P on this basis but neither metric looks cheap.

If you have the ability to hold cash, it seems prudent to wait to invest new monies at this point. The market may rise further in the short-term, but it looks like the risk-reward balance is out of equilibrium at this point. Volatility has been low and enthusiasm high; a reversal in either could lead to a better entry point.

Home Depot Rallies on Bad News

Low expectations have depressed the shares, but Home Depot’s financial position remains very strong. The company carries prudent levels of debt and generates very high investment returns. Management reported 22% returns on invested capital for the quarter (after considering operating leases the real number is in the high teens). These are admirable returns to post in this environment. Despite a slowing business climate, the company has been using its free cash flow to buy back shares. CEO Bob Nardelli knows a bargain when he sees one. Investors must have noticed.

EPS is still expected to grow by 4% and sales should be up around 12% for the full fiscal year. Frankly, I would expect worse. But the valuation is far from demanding: the shares sell at just around 12 times forward earnings and operating cash flow. For a premiere franchise like Home Depot, there seems to be a margin of safety built in to the current valuation, though not as much after the recent run-up.

One problem I had with their reported results today: no cash flow statement. It’d be nice to see a cash flow statement in the press release. This would help us gain a clearer picture of what went on during the quarter and first nine months of the year. Maybe next time, Bobby.

Disclosure: I own shares for clients as well as personally.

Expedia Still Looks Attractive

Expedia (EXPE) released earnings yesterday and results were essentially flat year-over-year. The international business continued its stellar growth and actually helped dampen some of the weakness in the domestic business. Hotel revenue was up smartly but air revenue was down significantly. Expedia cites “record industry load factors” as the problem there. What this means is that there is currently high domestic demand for air travel, resulting in fewer unfilled seats. And because of high demand the airlines don’t need companies like Expedia to help them unload hard-to-fill seats, as was the case a few years ago following 9/11. This trend is likely to continue for the foreseeable future, but should be mitigated by higher hotel revenues and continued growth internationally.

During the third quarter, they bought back nearly 5% of outstanding shares at bargain prices. The bulk of this was done in July at average prices of just over $14/share. This makes each slice of the pie bigger for shareholders who hang on. Expedia issued a small amount of debt (which is just 8% of total capital) to accomplish such a large buyback in a single period, but I think this was done opportunistically because management saw the shares as cheap. Look for more of this in the future, as an additional 20 million-share repurchase has been authorized. Barry Diller has a controlling (55%) interest in the business so you can bet he’s got shareholder’s interests in mind.

On the surface, Expedia does not look cheap, trading at nearly 17 times next year’s consensus earnings estimates. Yet reported earnings sometimes do not tell the whole story. I see the company as a cash machine that is being run for the long-term benefit of shareholders. The company’s free cash flow yield (free cash flow per share divided by the share price) is over 16%. This is the same as saying that Expedia trades for about 6 times free cash flow per share. The company also holds $946 million, or 17% of its market value, in cash on the balance sheet. A private owner looks at the cash the business generates, not the “earnings” the company reports. To a private buyer, these would be attractive figures especially given the growth opportunities that lie ahead.

Disclosure: I own shares for clients as well as personally.Biovail's Has a Strong 3Q - Can It Last?

That, as I’ve written about before, is the key question. For the first nine months, Wellbutrin XL revenues were up almost 40% and accounted for 72% of the company's year-over-year product revenue growth. In all likelihood, this key product, which holds a nearly 60% share of new prescriptions in its market and represents 41% of the company's product revenues, will have generic competition come on line that could seriously impair this position going forward. If not later this year, early next year seems increasingly likely. The conservative investor would factor a precipitate drop in Wellbutrin XL revenues into future cash flow and EPS calculations. How much is unclear, but when generic competition came online for Wellbutrin SR in Canada, prescription volume dropped 32%.

The Oil Industry's Cautious Investing

What worries me is that this report could provide Democrats with added leverage in getting some sort of “windfall profits tax” out of these companies. That would be just what we need – more government involvement in private business (yes, this is sarcasm). Where was the government a few years ago when some of these companies were barely making their interest payments? Will they return these windfall profits back to the energy companies when (if) prices decline? It seems like the memories of our legislators are entirely too short. In the past, the oil and gas industry has been one of boom and bust cycles. Now that industry executives have wised up and are wading somewhat cautiously into new investments while prices are high, they may get punished by the government in the form of higher taxes. My advice to those who want a windfall profits tax? Leave the market be and go read up on basic economics.

Returns Are Lower During Gridlock

It seems the prominent view that gridlock is good for the stock market is one that continues to be held by big investors. In this weekend’s Barrons, the cover story indicates that a common theme now being echoed among "big money" investors is that gridlock is good for the stock market. This is a belief that many hold, but one which has been called into question by a recent study published in the Financial Analyst’s Journal.

Gridlock is considered to be the state of government where the Senate, House, and Presidency are not held by the same party. The thesis behind “gridlock is good” for the stock market is that fewer legislative changes will take place in this situation, which reduces economic uncertainty.

The popular press has mentioned the “gridlock is good” argument fairly consistently, it seems without the proper data to back it up. The study I mentioned provides evidence that a government controlled by the same party – what they call “political harmony” – has enjoyed higher equity returns with lower volatility than during periods of gridlock. "Harmony” returns have been from 22% higher for the smallest companies to 0.5% higher for the largest companies - versus periods of political gridlock.

Furthermore, the study shows that the smaller-company “premium,” where small cap stocks have historically provide higher annual returns than large cap stocks, occurs in periods of political harmony (up 27.03% versus 4.65% in gridlock), and that large-cap stocks have actually outperformed smaller ones during periods of gridlock by nearly 4% annually. These results are independent of monetary conditions that existed during these periods, so they are significant.

On the other hand, the study found that fixed-income returns and volatility were higher during periods of political gridlock. This was mainly the result of interest rate changes during these periods.

I find it fascinating when a long-held, ubiquitous belief is shown to be wrong. This illustrates why its important as an investor to know why we hold the beliefs that we use in making investment decisions. They could very well be unfounded, or worse yet, wrong.

Investing Rationally

- Bill Miller, CFA

Biovail - A Value Trap?

Biovail (BVF) is trading at its lowest P/E, price/sales, and price/cash flow multiples since 2001. Net profit margins have been volatile, so based on average net profit margins of the past five years I calculate the stock as trading (cash stripped out) at under 8 times earnings on expected revenues of $950 million for next year, which represents a 6% drop from this year. Based on the factors above, it looks like the stock could use some serious consideration.

But what is the market telling us about its future prospects? Using a discounted cash flow model and a high discount rate (due to its business risk), it appears the market is pricing Biovail as if owner earnings (earnings minus CapEx plus depreciation) are going to be cut in half in the near future. This is entirely possible, mind you, as its primary revenue generator, Wellbutrin, accounts for 38% of its sales and it may lose market exclusivity for that one sooner than expected. Yet the company does have other drugs in the pipeline that could replenish this $300 million shortfall within a reasonable amount of time.

Biovail takes successful existing drugs that have come off-patent and makes them better. These reformulations are provided 3 years of market exclusivity, so there is considerable operational risk here. The company continually needs to come up with new ideas in a cost effective manner to growth profitably. Results have been volatile – certainly not as predictable as a seller of razor blades.

This lack of predictability makes Biovail a risky holding if the time horizon is long-term. To buy Biovail is to believe that the company will innovate in the future as they have in the past – with more and more drugs. They’ll need an increasing number of products at least every 3 years to continually grow their revenue base. Certainly, they have no competitive advantage in each individual product beyond market exclusivity. Yet perhaps they have an advantage in oral drug delivery technologies they use in their reformulations.

In order to invest in Biovail, I would need a reasonably good understanding of how sustainable the advantages are, if any, in the technology that Biovail uses. To me, it doesn’t seem like controlled release, graded release, enhanced absorption, rapid absorption, taste masking and oral disintegration technologies would be that difficult to copy. If they are easy to copy, the company’s only strength is in its ability to take an old drug, improve it before everyone else and get it to market the quickest. In this case, it's hard to evaluate sustainability into the future.

On top of these considerations, the company is under investigation for insider trading, financial disclosure and reporting, as well as product marketing practices. Yet the numbers make Biovail one to keep an eye on.

Companies Should be Viewed As Investment Conduits

We think that the best way to view a company is as an investment vehicle. This is what corporate management is paid to do – invest shareholder capital in areas where attractive investment returns are (hopefully) available.

At its base, a business invests capital in a collection of projects, products, or services and hopes to earn a return commensurate with the risk taken. It wants to earn a return on its invested capital – that is, equity and debt invested. And over time, the business will create wealth if it can earn above its cost of capital.

For a simple example, we’ll ignore taxes and consider a piece of real estate worth $1 million. Perhaps the buyer puts down 20% ($200k) of the purchase price, leaving $800k to be financed with debt at an 8% interest rate. So, the debt portion must earn enough in rent to pay costs plus an 8% (net of tax) payment to at least break even. That is, costs (maintenance, management, insurance, taxes, etc.) plus $64,000 to pay the principal and interest (P&I) on the loan. This is break-even on the debt portion.

The equity (20%) portion is a little trickier since it doesn’t actually have an explicit cost. Yet according to economic theory, this portion should be assigned an opportunity cost. For example, the opportunity forgone to invest in a similarly risky stock or bond that would earn 10%. Thus, this portion should earn costs plus 10% to earn an economically break-even return – $20,000 after costs.

In order to earn an excess economic return, returns must be greater than the weighted-average of these capital costs – [(.20x10%)+(.80x8%] = 8.4% after costs to break even in economic terms. So if the investment earns 10%, there is a 1.6% excess return (10%-8.4%). This is how economic wealth is created.

Many companies do not earn long run returns above their cost of capital, so how do they go on living? Certainly if it can’t pay its debts it should be bankrupt! Well, as I mentioned, the equity portion of capital does not really have an explicit cost, so a company can still cover its explicit debt costs while eroding the returns to equity.

Same thing in the real estate example. If it only earns 7% on the entire building after costs, it still has $70,000 to cover the $64,000 P&I. Ignoring principal payoff and appreciation, this leaves only $6,000 for the equity portion – a 3% return on the equity. If such a situation is expected to continue, this capital would be better employed in a money market account earning 5%. The exact same concept applies to publicly traded companies, albeit on a more complicated scale.

The bottom line is that we want a company to, say, borrow at 7% what it can invest at 15%, earning the “spread” of the investment return minus its cost of capital. This is, at its base, what every company is trying to do whether it sells steel, toilet paper, tax preparation, or owns real estate. Earning a return on its investments above the cost of the funds in the long run generates economic value for shareholders.

Fund Flow Update

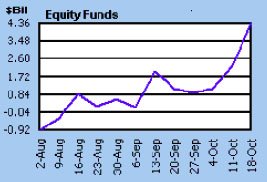

During this past week ended October 25th, another $1.6 billion flowed into equities, $1.1 of this into domestic funds. During this period, money market outflows totaled over $9 billion. The Dow is up 4.1% since the end of September – the performance chasing (and perpetuating?) continues!

Investors Still Chasing Performance

After a dismal second quarter for the broad markets, $5.41 billion were withdrawn from domestic equity funds during the third quarter (through September 30th). Yet the third quarter was a very strong one for the markets, with most domestic indexes rising by over 5%.

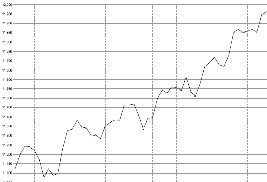

Over just the last two weeks (through October 18th), $6.57 billion went BACK IN to domestic equity funds! I've attached a couple charts. One is the equity mutual fund flows chart and the other is the Dow Jones Industrial Average price chart over the same period. In the equity funds flow chart, you can see the inflection point where money begins to pour back in. It happens to be just a couple days after the end of the quarter, after quarterly performance numbers hit the news media. The last couple weeks have also seen lots of talk about the Dow Jones Industrial Average reaching new highs.

Talk about performance chasing!

Importance of Evaluating Investment Mistakes

By not evaluating past mistakes, they may commit the same ones again. Current stock holdings might have above-average risk and be prone to similar problems to those of the past holdings. Maybe the companies are benefiting from some short-term industry tailwind or the stocks have “momentum” and are being bid up at increasingly high prices that are not justified by the fundamentals.

It is crucial during good times to evaluate past mistakes and frame these against your current holdings. Are there similarities? Did your past mistakes have too much debt? Were they commodity driven? Was management dishonest? What did you not see then that, if known, would have protected you from the eventual losses?

Don’t become complacent with recent results buoying investor sentiment. Now is the time to protect some of your gains and, if it makes sense, shift out of the riskier stocks you may now own. Look at valuations and earnings quality, the competitive strengths and weaknesses of the business and its ability to withstand adverse economic conditions, and understand the primary risks facing the company.

The stock market has a way of humbling egos. As Warren Buffett has said, you're not right because the market says you're right, you're right because your reasoning and analysis are correct.

An Educational Bargain?

The company operates the largest private university in the country (University of Phoenix) and offers educational programs and services at 100 campuses and 159 learning centers in 39 states, Puerto Rico, Washington DC, Alberta, British Columbia, Netherlands, and Mexico. Management controls the company, as the founder and his son own all of the voting shares. This can be good and bad, but overall you can bet they're watching out for company interests and not taking undue risks with the capital that represents a significant portion of their net worth. The company carries no debt and its returns on capital have averaged in the high 20s over the past 10 years (over 40s in the last couple). Of course, restatements may affect the return on capital numbers, but not the fact that they carry no debt on the balance sheet (though there are about $120M of operating leases off-balance sheet).

Upon cursory examination, this looks like a good value at 13 times forward earnings and a free cash flow yield of 8.3%. They’ve been using that discretionary cash to buy back shares the last several years, which has more than offset the dilution from option exercises. With the growth opportunities that lie ahead, this could be a screaming bargain. But how reliable are the numbers? I’ll post more thoughts later.

Is the Market Starting to Capitalize Peak Earnings?

If a slowdown is years away and profit margins and earnings have longer to run, the companies may be worth more. But if we have a slowdown, profit margins will erode, with earnings taking a corresponding hit. I may be wrong for a while, but I’m willing to bet longer-term that because the business cycle is at or near a top, cyclical industries in general are not the best place to be investing new monies at this time.

A Thought with the Dow Nearing 12,000

- John Hussman, Ph.D

A Few Words on Our Investment Philosophy

In most cases, we’re trying to determine what the value of a company is to a private market buyer in a negotiated transaction. But we’re not going to pay that price. We want to buy the company at a (hopefully large) discount from this value. After all, as a minority shareholder, we can’t have any influence on what the company does with its excess cash flows. That is, the cash beyond what is needed to sustain and grow the business given available reinvestment or new investment opportunities. A private market buyer would be able to go in and, say, invest in public securities or pay out the excess cash to himself. And thus he should have to pay more for this control. Sometimes, we can profit from this difference between our position and his. We look at adjusted book values, normal earning power, free cash flow generation, and other metrics to determine what a company is worth.

As Charlie Munger has said, “It’s not a competency unless you know the edge of it.” We can’t know everything, but we try to be aware of what we don't know. We look for businesses we understand that are being run by honest, able managers whose personal stakes in the success of the company are high. If we can buy these companies below what they are worth, we should do reasonably well over the long-term.

We’re not worried about near-term market prices, just investment risk – something going wrong with the business. If we find value, we feel comfortable making a purchase and waiting for the market price to take care of itself. If the company’s management continues to create value by generating satisfactory incremental investment returns, the market price should rise accordingly, albeit non-linearly with intrinsic value. This is not to say that we aren’t concerned with market prices, we are just not focused solely on them.

Also, some ideas posted here are not meant to be long-term. These could be called “trades.” But such trades are taken with a long-term perspective.

Quality of Earnings Deteriorating?

Why could this be worrisome? Well, a difference between GAAP earnings and pro forma earnings indicates the use of below the line, one-time “nonrecurring” charges that are often ignored when comparing period-over-period changes in earnings. Some analysts will simply back out the one time charge, adding it back to earnings (pro forma) since the charge is supposed to be non-recurring, unusual or extraordinary. The problem is, sometimes these charges should not be ignored and actually should, at least in part, be considered part of a company’s ongoing operations, despite their apparent one-time or unusual nature.

To see how these one-time charges affect economic value, watch the cash flow statement and read the footnotes. These charges, though one-time from a GAAP perspective, will continue to show up in cash flow as companies pay for severance packages or restructuring costs, for instance. Or they may be non-cash in nature, such as asset writedowns, which won’t affect cash flows until the asset is sold, or goodwill impairment.

Note that these “nonrecurring” charges can also be used to manipulate earnings. Taking the hit in the current quarter may benefit GAAP earnings in the next. Sometimes this will occur in the form of a “big bath” where, when times are tough, a company might “move” all of the next few periods’ plant shutdown costs into the current period, so that future “earnings” are not crippled by these expenses. It’s the “Let’s get all the bad stuff out of the way now” idea. This can come in the form of asset writedowns, layoffs, restructurings, etc., whose actual economic effects are not really confined to a single period.

If this widening continues into the third quarter, it could lead to a troubling trend. Stick with companies that have high quality earnings and where cash flows and earnings tend to approximate one another. If there is a persistent sharp disconnect, the company may be trying to hide trouble.

More on Dow Chemical

(continued from previous post)

The 4% dividend yield is a nice pad to total return. Over at least the past 17 years, the company hasn’t cut or reduced its dividend, which has grown at an annual rate of a little over 3%. The company is watching costs, having shut down more than 50 manufacturing facilities across the globe over the last three years amidst record profitability. And they’re using cash to pay down debt and buy back shares. Yet this has happened before, most recently from about 1994 through 1998, and from there debt levels and share count grew again.

We know the third quarter is likely to be a little rough, as the company will be taking about $600 million in charges for severance and asset writedowns as a result of plant closings. Look for earnings to be boosted in future periods, as this writedown will hit earnings in the third quarter of this year and not affect them in future periods. Don’t be fooled, though, as actual severance and plant shutdown costs will continue to impact the company’s cash flows into the future.

Let’s look at another metric, the current forward price-to-sales (P/S) ratio, which is around 0.75. This is near the lows of the past 10 years and most similar to the lowest forward multiples experienced in 1995-96 for the expansion years of 1996-97. Coincidentally (or not), the period most similar to now in level of margins and ROE was 95-96. The average forward P/S multiple during those years was under 0.90 (since 1995 Dow’s average P/S ratio is 1.00) , while Dow’s P/E ratio averaged 9.5, which looks strikingly similar to now. What does all this mean?

Purchased at the low prices of 1995-96, Dow would have returned about 8.6% annually to date (including the 10-yr average dividend yield of 2.6%). The S&P 500’s total return over that period is around 10% annually.

Historically, it has been more profitable to buy cyclical companies when P/Es are high and profits are bottoming. In this case, Dow has a low P/E ratio and its profits are (probably) at or near a peak.

If you think the stock has upside between now and January but don’t want to invest the cash, write a Jan 40 put and buy a Jan 40 call. Based on current prices, you’ll effectively own the stock at a little over $39 (slightly over market) but without any cash outlay. Be aware that you’ll need to have the cash to cover the trade in the event the stock is put to you come January.

A Look at Dow Chemical

This is a cyclical company that lacks an economic moat. In other words, it is largely not in control of its own destiny. It has high returns during economic expansion (when demand exceeds supply) and experiences poor returns during contractions (when demand weakens, or supply brought on during expansions exceeds demand). Roughly 50% of revenues come from specialty chemicals and plastics. These businesses are less cyclical than other, basic chemical lines but all segments remain sensitive to the economic cycle.

Especially in its North American operations, the company has little control over its resource costs and is only able to pass cost increases along to customers when demand is high. Thus, when economic activity slows and costs in increase the company’s margins get squeezed. Of course, this works both ways. Both oil and gas, which comprised almost half of Dow’s total costs in 2005, are down dramatically in price as of late. This is likely to lead to some margin gains and maybe even to an upside earnings surprise in Q4, perhaps even in Q3. But these gains may be fleeting.

Operating and net margins appear to be at cyclical highs (18.5% and 9.5%, respectively, versus a 14% and 5.2% 7 year average), as does return on equity (ROE), at about 26% currently, versus a seven-year average of 15%. The current numbers are direct evidence of pricing power during a period of high demand. Looking back as recently as 2001 and 2002 (recessionary conditions), Dow’s operating margins were near 10% and net margins were negative.

The market doesn't capitalize peak earnings, so let’s use the above numbers to “normalize” Dow’s earnings over an economic cycle. That is, average out the swings in profitability that result from the cyclical nature of the business. Using the 7-year average ROE of 15% times the current (2Q 2006) book value of $17.52, I get a “normal” net income number of $2.63. Using the normalized net profit margin based on projected 2006 sales we arrive at about the same number. At today's price, this puts Dow at nearly 15 times normalized forward earnings. This happens to be right around Dow’s average P/E since 1990.

(look for more on Dow in coming days)

A Contrarian Thought for (another) Record DJIA High

- Jean Jacques Rousseau

A New High - Now Let's Move On

General Motors (GM) is the average’s top performer year-to-date, up 74% and responsible for about 1.7% of the DJIA’s YTD performance. Looking deeper at the Dow’s YTD performance, we can see how the price-weighted average calculation method can affect its returns. Merck (MRK), now a $42 stock, is the second highest contributor after GM – up over 32% year-to-date and responsible for about 0.9% of the DJIA returns. The third largest contributor, Boeing (BA), an $82 stock, is up only about 17%, yet has contributed the same amount as MRK (about 0.9%) to the Dow’s returns. Despite Merck's returns exceeding those of Boeing by almost double, the effect on the DJIA is the same.

Note that the index in no way tries to overweight undervalued stocks or underweight the overvalued stocks. I don't know many money managers who determine a stock's weighting in a portfolio based solely on price.

Private Equity's Newest Bet

It’s a cash deal, which means that the newly private firm will be saddled with large amounts of new debt (Harrah’s market cap at the deal price is $15 billion) while assuming over $10 billion of existing debt. Interest expense currently totals around 25% of EBITDA. My primary worry in the near-term is that adding significantly to its debt load would limit its flexibility during a downturn.

True, at this point Harrah’s generates a healthy amount of operating cash flow that could service additional debt, but in recent years that cash flow has been used to fund considerable capital expenditures. Could more debt meaningfully restrict their ability, for instance, to develop their properties on the Vegas Strip to better compete with MGM’s upcoming City Center?

Typically, these private equity deals work out the best when a firm can slash costs, wringing out extra cash to pay down the new debt. Yet this could be detrimental to Harrah's, where capital spending is vital not only to maintain its growth track, but also to keep its casinos relevant and its competitive position in place.

It’ll be interesting to watch. With insiders owning over 4% of the shares, shareholders can bet the board has their interests in mind. Feel like a gamble? Go long Harrah’s shares and bet the deal goes through.

DJIA Flirts with a Record Close

This week, even on mute, it seemed like they were covering a horse race, not the stock market, as the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) neared its record close set back in 2000 (the S&P 500, by the way, has over 14% higher to go to best its all-time closing high of 1527.46). Case in point, CNBC added along the top of the screen a “DJIA within X pts of record close” banner and had the “breaking news” alert going during market hours. Meanwhile, guests were asked if and when we’ll get to that record close.

So what if the Dow nears its record close?! It accounts for only 25% of the broad market (as measured by the Wilshire 5000) and is composed of just 30 companies in the form of a price-weighted average. To calculate it, the 30 companies' stock prices are literally added together and divided by, as of today, 0.12493117. That gives us the index value seen every day. This means companies with the largest absolute prices in the index have the largest relative impact on performance. For instance, IBM, with an $82 price would have a larger impact for each percent move than Intel, with a $20 price. A 5% move for IBM is $4.10, but just $1.00 for Intel. Similar problems exist for market-value weighted indexes, such as the S&P 500 (which is now float-weighted). These types of indexes tend to underweight undervalued stocks and overweight overvalued stocks, the exact opposite of what should be done.

Forgetting all that for a minute, the DJIA has had a strong run in recent months. Over the longer-term the performance of the DJIA tends to approximate the broader markets, but year-to-date the Dow is above the S&P 500 by nearly 2 percentage points, and has had its best quarter since the third quarter of 1995. How to play this recent run-up? If you own Diamonds (DIA), now might be a good time to sell at-the-money or slightly out-of-the-money call options on your shares. Going out to December or January, you’ll earn a decent premium and are likely to have the chance to buy them back at cheaper prices before expiration.

Chesapeake's Smart Move

It's not often that you see a company sacrifice short-term numbers for the benefit of long-term wealth creation. With NYMEX natural gas prices hitting $4.20 (front month) Wednesday, CHK would still realize an over 100% cash operating margin (given cash costs are only about $2/mcfe). Yet management knows NG prices are on the low-end and that Mr. Market is likely to provide them with higher prices in the near future.

Meanwhile, today's press release updated us on their hedging position, which is even better than reported at year-end:

"The Oklahoma City-based company has locked-in prices averaging $9.24 per thousand cubic feet for about 92 percent of its expected production in the second half of the year. About 80 percent of Chesapeake's anticipated 2007 production is hedged at $9.92, and about 60 percent of 2008 production is contracted at $9.44." An enviable position to be in.

Great company. Buy it; the CEO has been doing so at prices higher than today's.

Disclosure: The author owns shares for clients as well as personally.